Peaceworks

He Kaupapa RongomauEdition One 2022

International Affairs

Nuclear threats, peace education, common security and Aotearoa:

A reflection on the 35th anniversary of New Zealand’s nuclear weapons ban, and what we can do now to prevent nuclear war and achieve global nuclear abolition.

By Alyn Ware, Peace Foundation International Representative

If you have been following the conflict in Ukraine, you will no doubt have noticed that not only has Russia been undertaking a horrific ‘military operation’ (war) attacking homes and killing civilians, but also that Russian President Putin has threatened nuclear war if NATO, the USA or any other country uses military force to try to stop him take over Ukraine. Russia is not the only one to blame for nuclear threats in Europe. The USA and other NATO countries have also played a role, with the modernization, development and deployment of nuclear weapons on submarines and in a number of NATO countries under options of first-use, coupled with an expansion of NATO closer and closer to Russia.

Collectively, Russia, the USA and NATO have over 12,000 nuclear weapons, most of them at least 10 times more destructive than the nuclear bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in WWII. If a nuclear war breaks out in Europe, the consequences would be catastrophic and unprecedented. It could result in the deaths of billions (yes – billions) of people and possibly the end of civilization as we know it. Europe is not the only region in which the threat of nuclear war is Increasing. There are also heightened tensions involving nuclear threats between North Korea and the USA, China and Taiwan, India and Pakistan and in the Middle East.

New Zealand peace organizations and the government have been very active in the past on nuclear disarmament, including by banning nuclear weapons through New Zealand’s ground-breaking Nuclear-Free legislation adopted 35 years ago on June 8, 1987. The rejection by New Zealand of nuclear deterrence was a powerful stand against the madness of Mutually Assured Destruction in the 1980s. But what can we do now?

Below is a short background on New Zealand’s nuclear weapons ban, plus ways in which we New Zealanders and our government can reduce the current risk of nuclear war and advance global nuclear abolition in the new global environment.

Peace education helped move New Zealand from being from a nuclear ally to anti-nuclear leader

New Zealand was a willing player in the nuclear arms race from the birth of the nuclear age in 1945 up until the mid-1980s. In 1945 most New Zealanders celebrated the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which we believed at the time to have been instrumental in ending World War II. Our country then joined a nuclear alliance with the United States, supported nuclear tests in the Pacific (with our military participating in some of them) and hosted port visits of nuclear armed ships from our allies, in particular the United States, to demonstrate New Zealand’s adherence to nuclear deterrence.

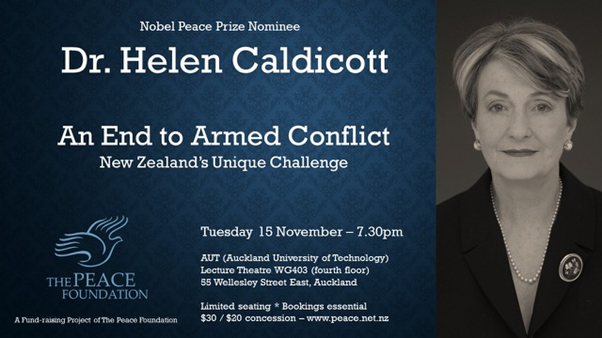

The Peace Foundation, from the time of its establishment in 1975, developed materials and organized events to educate public about the risks of nuclear weapons and the importance of abolishing them. One pivotal event, organized in cooperation with the New Zealand section of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW), was the 1983 New Zealand tour by paediatrician Helen Caldicott, who spoke to audiences of thousands in the main centres, as well as on prime-time TV. Helen’s visit stimulated many more doctors to join IPPNW – membership grew to around 30% of the population – and the further spread of neighbourhood and city-wide peace groups around the country.

The anti-nuclear movement grew to around 300 such groups following Helen’s visit. The Peace Foundation cooperated with other national organizations such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, New Zealand Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Committee, Peace Squadron, CANWAR (Campaign Against Nuclear Warships) and Peace Movement Aotearoa.

One of the education actions was to establish workplaces and cities as nuclear-weapon-free zones. By the time of the 1984 election, over 2/3rds of New Zealand’s city councils were persuaded to do so, sending a strong signal to the incoming government that a ban on nuclear weapons had strong support from around the country and from across the political spectrum.

Another key education activity undertaken by the Peace Foundation and partner organizations was to commemorate Hiroshima and Nagasaki Days – the anniversary of the nuclear bombing of these two cities in 1945. This included public events and classroom activities, such as telling the story of Sadako Sasaki, a girl who died from radiation exposure in Hiroshima. The storytelling was accompanied by teaching children how to make origami cranes – the Japanese bird of peace. Thanks to the Peace Foundation, the story of Sadako and the crane-making instructions were sent to every primary school in the country in a special issue of the School Journal.

Children learning origami crane making in school, 1982. Photo: Gil Hanly

The campaign also educated members of parliament from all parties about the nuclear threat and encouraged them to stand up in parliament for a nuclear-free New Zealand. This led to private members bills in parliament from opposition parties, one of which helped triggered the snap election of 1984. The conservative (National) government held a majority in parliament of one seat, and was about to lose a vote in parliament on an opposition bill to make New Zealand nuclear-free, due to the announced support for the bill by National MP Marilyn Waring. Prime Minister Robert Muldoon, a strong supporter of nuclear deterrence who once remarked that the failure of the USA in Vietnam was partly due to their ‘unwillingness to use the ultimate weapon’, called the snap election primarily to avoid this loss in parliament – and then lost the election.

The newly elected Labour government under the leadership of David Lange changed the course of New Zealand’s future by adopting a policy of banning nuclear weapons in our country, and enshrining this in law, which was adopted on June 8, 1987.

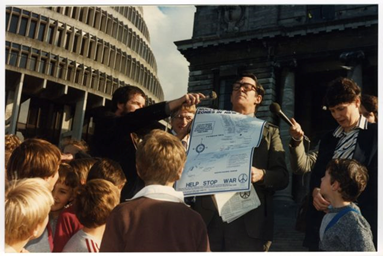

Larry Ross, founder of the New Zealand Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Committee, presenting a map of

nuclear-free local authorities to Helen Clark MP at the New Zealand Parliament in 1983.

United States opposition and the World Court case

When the Lange government announced the nuclear ban policy on assuming government in 1984, the United States launched a campaign of opposition, propaganda and intimidation against New Zealand that they thought would succeed in changing the government’s mind – as the US had done successfully with the Australian Labour government in 1983.

The United States argued that New Zealand had an obligation under the ANZUS Treaty to accept port visits of nuclear warships. When the Lange government disagreed, the US launched a campaign to isolate New Zealand in the Western diplomatic circles, ran misinformation campaigns including one asserting that Soviet submarines were taking over the Pacific as a result of New Zealand’s policy, applied economic pressure through a trade boycott, attempted to undermine the government through a false loan offer for Maori housing, threatened to suspend military cooperation and in the end suspended the ANZUS military alliance with New Zealand when our government refused to fold to the pressure.

The US assertion that the ANZUS Treaty required New Zealand to accept nuclear deterrence stimulated peace movement leaders from New Zealand, including members of the Peace Foundation and the International Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms (IALANA), to establish the World Court Project on Nuclear Weapons and International Law. This initiative succeeded in moving the International Court of Justice to consider the issue of nuclear weapons, and to affirm in 1996 that the threat or use of nuclear weapons is generally illegal and that there is a universal obligation to work for their elimination. (See Aotearoa-New Zealand at the World Court by Kate Dewes and Robert Green with foreword by David Lange).

The New Zealand Attorney General greets civil society supporters prior to giving New Zealand’s oral statement to the International Court of Justice in the 1995 nuclear weapons case.

The New Zealand Nuclear-Free Zone legislation – a global model

2020 is the 35th anniversary year of the New Zealand Nuclear-Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Act. This legislation not only prohibits nuclear weapons in New Zealand, it also prohibits ‘agents of the crown’ (government officials, members of the military and public servants) from aiding or abetting the production, deployment, testing, threat or use of nuclear weapons anywhere in the world.

The legislation also establishes a Minister for Disarmament and Arms Control (still the only one in the world) and a public advisory committee on disarmament and arms control (PACDAC) to advise the government on disarmament policy. Peace Foundation members have often served on this committee, and the government has on a number of occasions adopted and implemented recommendations from the committee.

Under the 1987 legislation PACDAC is also empowered to promote peace and disarmament education, including through the allocation of funding. Two funds – the Peace and Disarmament Education Trust (PADET) and the Disarmament Education United Nations Implementation Fund (DEUNIF) are now administered by PACDAC and have helped many education projects around the country.

In 2013, the Nuclear-Free Act was recognized by the United Nations and the World Future Council as one of the most significant disarmament policies in the world – winning second prize (the Silver Award) in the prestigious Future Policy Awards which were bestowed at the UN in New York.

Nuclear disarmament: Education on conflict resolution and common security

Nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence policies do not arise in a vacuum or by chance. Countries which possess nuclear weapons, or are under extended nuclear deterrence ‘protection’, do so by choice. They have threats to their security which they believe can be met by nuclear deterrence. In order to move them to end their reliance on nuclear weapons, we have to educate the governments and their public on how they can achieve their security in other ways – in particular through diplomacy, conflict resolution, common security and international law.

New Zealand has demonstrated a number of times that international conflicts and serious threats to security can be resolved this way, including conflicts relating to nuclear weapons. When the French government bombed the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbour in 1985 and then barred our exports to Europe in retaliation for New Zealand convicting two of their agents involved in the bombing, we successfully resolved the dispute through the UN mediation service. And on the wider issue of French nuclear testing in the Pacific, we lodged cases in the International Court of Justice, which helped move France to end the nuclear tests and close down the test site.

Many peace and disarmament organizations have highlighted that diplomacy, conflict resolution and common security mechanisms should have been used to prevent the Ukraine/Russia conflict escalating to war, which has increased the threat of nuclear war. (See Abolition 2000 Member organizations oppose Russian invasion of Ukraine). And many continue to promote a common security framework to help resolve, not only the Ukraine conflict but other serious conflicts around the world, some involving nuclear-armed countries.

Common security builds security between nations through international law, diplomacy and conflict resolution. It is based on the notion that national security cannot be achieved or sustained by threatening or reducing the security of other nations, but only by ensuring that the security of all nations is advanced and that conflicts between them are resolved in ways that meet the needs of all. The application of common security to today’s critical issues is explored in the recent report Common Security 2022 released by the Olof Palme International Centre. Helen Clark, former Prime Minister of New Zealand, is one of the expert commissioners that prepared the report.

Helen Caldicott, who galvanized the New Zealand Peace Movement in 1983, was invited back to New Zealand by the Peace Foundation in 2016 to give a keynote address on nuclear disarmament and an end to war.

The continuing importance of peace education

The introduction and implementation of peace education into New Zealand schools, and a strong priority on peace education in the community, is one of the reasons why New Zealand’s nuclear weapons ban has cross-party support, and why New Zealand has shifted from being a militaristic country to one of the most peaceful in the world. New Zealand now ranks 2nd on the Global Peace Index.

Since 1980, the Peace Foundation has been running peace and disarmament education programmes in schools. These found support from the government in 1987 by the adoption of Ministry of Education Peace Studies Guidelines for Schools, followed by government funding for such programmes. The programmes help students to develop skills, knowledge and attitudes to resolve conflicts in their lives and support peace and conflict resolution in wider society.

See Peace education and common security: Positive peace from schools to the world, Alyn Ware Right Livelihood Lecture, Zurich, May 13, 2022.

The Peace Foundation organizes a human peace sign in the Auckland Domain in June 2017 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of New Zealand’s nuclear free legislation.

What else can the government do to prevent nuclear war and advance nuclear abolition?

There are a number of opportunities for New Zealand to advance nuclear risk reduction and disarmament in key international forums this year.

- Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons: Time to export our nuclear-free policy.

More than 60 countries are now parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). None of the nuclear armed or allied states are members, so the Treaty does not have direct impact on them. However, building on the experience of our nuclear-free legislation and divestment, NZ could encourage other States parties to the TPNW to adopt similar measures, including to ban transit of nuclear weapons, end public investments in the nuclear weapons industry and establish a Minister for Disarmament. It’s time to export our nuclear-free policy.

- Non-Proliferation Treaty

In August this year, States parties to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) – which includes the major nuclear armed states and their allies – will meet at the United Nations for 4 weeks to discuss nuclear risk reduction, non-proliferation and disarmament. This is an excellent opportunity for New Zealand and other non-nuclear countries to engage with the nuclear-armed countries and allies, to convince them to take important nuclear risk reduction and disarmament measures including no-first-use, commencing negotiations on a framework to eliminate nuclear weapons, and adopting a commitment to achieve the total elimination of nuclear weapons globally no later than the 100th anniversary of the United Nations. For background and more comprehensive recommendations, see NWC Reset: Frameworks for a Nuclear-Weapon-Free World, and No-first-use of nuclear weapons: An Exploration of Unilateral, Bilateral and Plurilateral Approaches and their Security, Risk-reduction and Disarmament Implications, two civil society papers for the 10th NPT Review Conference.

What can you/we do?

There are a number of things we can do help end the nuclear threat and advance nuclear abolition.

- Endorse the Open Letter Fulfil the NPT: From nuclear threats to human security;

- Join the Peace Foundation to receive PEACEWORKS with updates on school, youth and international programmes;

- Make a donation to support the international peace and disarmament work of the New Zealand Peace Foundation and its International Representative undertaken in cooperation with the Basel Peace Office;

- Visit the UNFOLD ZERO blogs and/or sign-up for the UNFOLD ZERO newsletter to receive updates on United Nations focused actions/initiatives for peace, disarmament and common security;

- Take part in the Move the Nuclear Weapons Money campaign to help shift budgets and investments from nuclear weapons to instead support peace, climate action and sustainable development.

Other news

Family Programme

“When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace” Dalai Lama

Our Mindful Family Communication for Well-being programme aims to achieve this goal of strengthening the power of love through empowering parents with effective communication and Emotion Coaching skills to help them feel more connected to their own lives and therefore their children’s.

Peace Education for schools

The Peace Foundation has some exciting news to share! As from 2023 the Cool Schools Peer Mediation Programme for primary schools and our Leadership through Peer Mediation Programme (LtPM) for secondary schools, will have updated and culturally responsive resources for both ākonga and kaiako to use in schools. This will include new peer mediation training videos, manuals for teachers and programme coordinators plus workbooks for students.

Upcoming Events

Youth Peace Week

Youth Peace Symposium

Recent Comments